A-maze

Github pages site for A-maze.

View the Project on GitHub vboyce/Maze

Thought pages

What is A-maze?

An argument for 'redo' mode

New delay feature for 'redo' mode

Experiment design

Parameter considerations

Practical pages

Install instructions

Basic use

Parameters

Advanced options

Using Ibex for Maze

Hosting an Ibex-Maze Server

Why I run experiments in ‘redo’ mode

The Maze task, as traditionally presented, does not tolerate mistakes. If you make a mistake and select the distractor instead of the correct word, you’re done for that sentence. You see an error message, and start the next item.

However, this can cause some problems. For one, if your distractors early in the sentence are often plausible, you lose a lot of data when many of your participants screw up on word two, and so you don’t get any data from them for the rest of the sentence. For another, your item length is limited by how long people can get everything right, which makes multi-sentence items basically impossible.

So, one potential fix for the first problem would be to write better distractors (with some combination of better programmatic choices and some hand-checking and editing). Or, we could just make Maze forgiving.

The later approach, is, as it turns out, easy to code. When a mistake is made, instead of discontinuing the sentence, we display an error message, and wait until the participant clicks the correct button. Then, we continue with the sentence. We record the error, and both how long it took to click the wrong button and also how long until the correct button. In the Ibex implementation of Maze, the toggle for this is called ‘redo’, and you can turn it on for an entire set of items by adding the following near the top of your experimental file.

var defaults = ["Maze", {redo: true}];

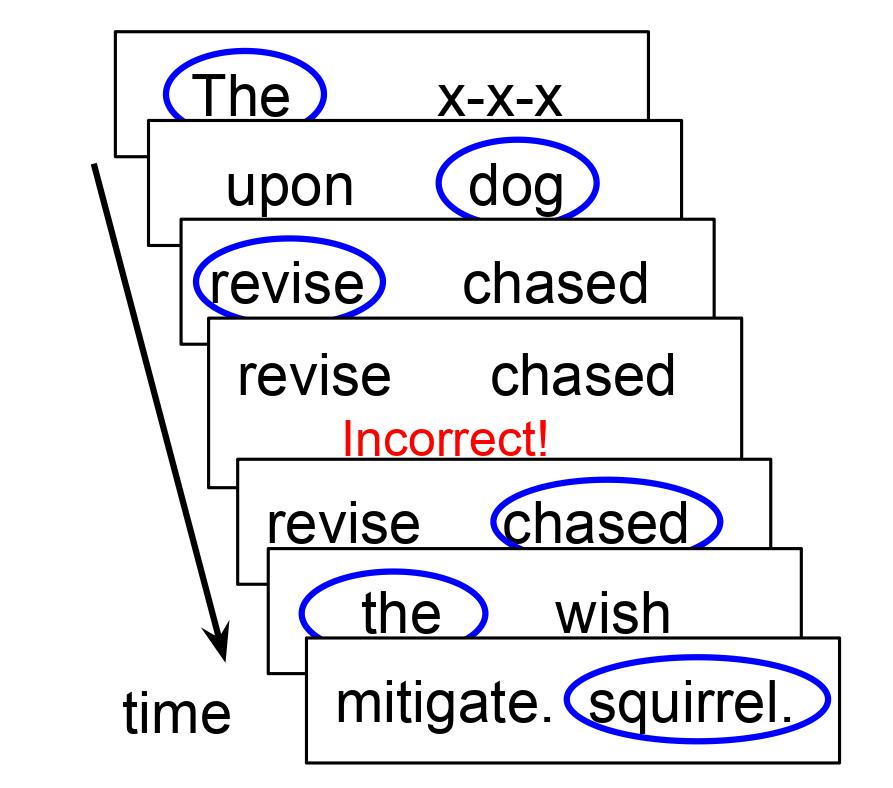

This leads to a Maze task that looks more like the following. (Selected words circles in blue.)

I initially added this setting as a way to check materials (so, the experimenter could go through and note where things were iffy, continuing to check a sentence even after they misclicked), but I quickly convinced myself that this was just a better way to run experiments.

For one, this gives me a much better idea of how participants are doing. I can get a better picture of how often participants are choosing correctly, because I have all their clicks, so it’s easy to tell who is getting around 50% correct (and therefore randomly guessing) and exclude their data. There’s no longer the confounding between worse distractors early in sentences and worse participants early in sentences (before the random clickers make mistakes and stop seeing the sentence).

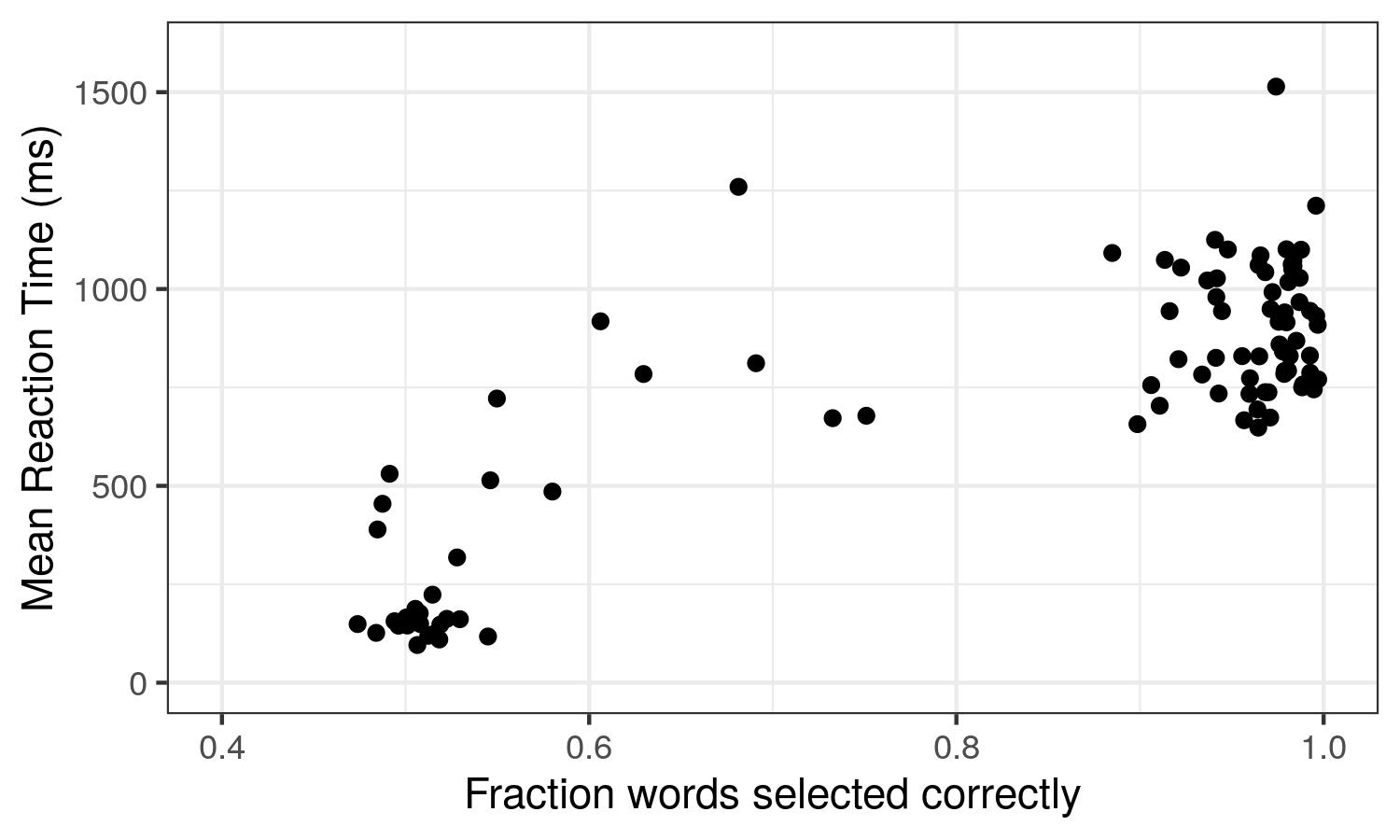

As an example, here’s the correlation between accuracy on the Maze task (fraction of words chosen correctly) and mean RT on a recent experiment of 100 participants recruited from MTurk. As you can see, some participants jam the keys to get through the experiment quickly – they have mean RT around 100-250 ms and accuracy around 50%, consistent with random guessing. We don’t want data from these participants; it’s useless. However, there’s also a lot of participants with accuracy >90% range and RTs around 1 second. This is the data we want. By using redo mode, we can get good measures of accuracy (free from the confound of “did they make a mistake on word 2 because their error rate is 50% or because the distractor at word 2 was poor?”) and use this to filter participants. I use 80% accuracy as the cut-off for including a participant’s data in analyses.

Additionally, I can run multi-sentence materials where information builds on previous sentences because even if they make mistakes, participants still saw all the information and can follow the text.

I also can potentially use post-mistake data in analyses, which could increase the useable data considerable. Clearly, RT data from right after a mistake might be contaminated (who knows how mental processes involving errors might influence things), but at some point farther after a mistake it should be basically trustworthy. And if there happen to be a lot of errors at word 2, and the critical word is word 10, having that data for word 10 seems useful.

Even if you don’t analyse things after mistakes, it still probably makes for a better participant experience because mistakes don’t feel so final. Being able to correct mistakes can mitigate both the accidental misclicking (‘but I meant that other word’) and plausible distractors (‘it seemed like a fine continuation, why was it wrong?’).

It’s very easy to label and filter out data after mistakes, if you want to exclude it from analyses. The below R code shows how to label words that are after mistakes and remove words within 2 after a mistake. A similar approach could filter out all data after mistakes.

data_filtered <- data %>%

mutate(word_num_mistake=ifelse(correct=="no", word_num,NA)) %>% #label the word number for errors

group_by(sentence, subject) %>%

fill(word_num_mistake) %>% #within each grouping, propagate real values down over NAs

ungroup() %>%

mutate(after_mistake=word_num-word_num_mistake, #calculate how many words since last mistake

after_mistake=ifelse(is.na(after_mistake),0,after_mistake)) %>% #if before mistake, fill with 0

filter(correct=="yes") %>%

filter(!after_mistake %in% c(1,2)) #filters out words one or two words after a mistake